Henderson–Hasselbalch Calculator

Buffer chemistry shouldn’t feel like a maze. With this Henderson–Hasselbalch calculator you can plug in any three values and get the fourth in a heartbeat—pH, pKa, conjugate base concentration [A⁻], or acid concentration [HA]. It’s built for students in a hurry, researchers under a deadline, and anyone who wants clean answers without wrestling with logs by hand.

Where the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation shines

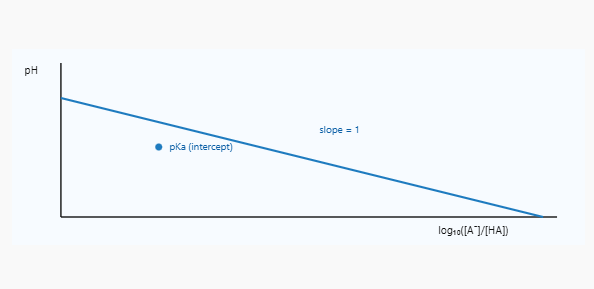

Think of a buffer as a seesaw. On one side sits the weak acid HA, on the other its conjugate base A⁻. Add acid and the base takes the hit. Add base and the acid steps in. The Henderson–Hasselbalch equation ties the balance to pH with a straight line on a semi-log plot. You can predict how much each side needs to keep the pH steady, or you can reverse the logic to discover the pH from what you have on hand.

When you scale concentration on a log axis the relationship turns simple. Increase the ratio [A⁻]/[HA] by a factor of ten and the pH rises by one unit. Cut that ratio by ten and the pH drops by one unit. You can see why the equation is a favorite in biochemistry, environmental testing, and pharmaceutical labs.

How to use the Henderson–Hasselbalch calculator

You don’t need a long protocol to get value from the tool. Enter any three values and it returns the missing one. Units for concentration can be M, mM, µM, or nM. The calculator normalizes everything internally, then displays concentrations in molarity for clarity.

- Choose what you want to solve for—pH, pKa, [A⁻], or [HA].

- Provide the other three inputs. You may enter either pKa or Ka if you prefer.

- Review the results panel. You’ll see the calculated value plus the ratio [A⁻]/[HA].

- Copy the table to your clipboard or download a CSV for your notes.

Tip: The buffer works best when pH sits within ±1 of pKa.

The formula, variables, and units

The Henderson–Hasselbalch relation originates from the acid dissociation equilibrium. Rearranging the Ka expression and taking the decimal logarithm yields a compact form:

pH = pKa + log10([A⁻]/[HA])

You’ll use four quantities:

- pH — the hydrogen ion activity measure. Unitless.

- pKa — negative log of the acid dissociation constant Ka. Unitless.

- [A⁻] — concentration of the conjugate base. Use M, mM, µM, or nM.

- [HA] — concentration of the weak acid in the same unit family.

| Symbol | Meaning | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| pH | Acidity of the solution | Calculated from hydrogen ion activity |

| pKa | Strength of the acid | pKa = −log₁₀(Ka) |

| [A⁻] | Conjugate base concentration | Use the same unit as [HA] |

| [HA] | Acid concentration | Use the same unit as [A⁻] |

| ratio | [A⁻]/[HA] | 10^(pH − pKa) |

pKa depends on temperature and ionic strength. If your experiment runs far from room conditions, use a pKa value matched to your temperature range.

Worked examples you can copy

Example 1 — Predict the pH of an acetate buffer

You prepare a solution with 0.20 M sodium acetate and 0.15 M acetic acid. Acetic acid has pKa ≈ 4.76 at 25 °C. What pH should you expect?

Use the equation directly.

pH = 4.76 + log10(0.20 / 0.15)

= 4.76 + log10(1.333…)

= 4.76 + 0.1249

pH ≈ 4.885

The calculator returns the same result and shows the ratio 1.33 for validation.

Example 2 — Find the acid concentration needed to hit a target pH

You want pH 7.40 with a phosphate buffer using the H2PO4−/HPO42− pair with pKa₂ ≈ 7.21. You have 50 mM of HPO42−. What [H2PO4−] do you need?

ratio r = 10^(pH − pKa) = 10^(7.40 − 7.21) = 10^0.19 = 1.548 [A⁻] = r · [HA] → [HA] = [A⁻] / r Given [A⁻] = 50 mM → [HA] = 50 / 1.548 = 32.3 mM

Enter pH 7.40, pKa 7.21, conjugate base 50 mM, solve for acid. The tool reports 32.3 mM.

Example 3 — What’s the pKa from a titration midpoint?

During a titration of lactic acid the pH at half-neutralization reads 3.86. At that point [A⁻] = [HA] which means the log term equals zero. pH equals pKa. So pKa ≈ 3.86. This trick saves time when you have good titration data.

Example 4 — Small pH nudges without changing volume

Say your Tris buffer sits at pH 7.95 while you need 8.10. Tris pKa near room temperature is ~8.06. You can estimate which side of the pair to add. Compute both ratios.

At pH 7.95: r = 10^(7.95 − 8.06) = 10^(−0.11) = 0.776 At pH 8.10: r = 10^(8.10 − 8.06) = 10^( 0.04) = 1.096

The base fraction must increase since r climbs above 1. Add a tiny aliquot of base form or remove a touch of acid form. The calculator quantifies the move when you plug in your total concentration and volume.

Quick reference: ratios, pH shifts, and rules of thumb

| Target − pKa | Ratio [A⁻]/[HA] | Reading the buffer |

|---|---|---|

| −1.0 | 0.1 | Acid form dominates. Buffer still workable. |

| −0.3 | 0.50 | Slightly acidic bias but balanced. |

| 0 | 1.0 | Maximum capacity per mole near this point. |

| +0.3 | 2.0 | Leans basic with good stability. |

| +1.0 | 10 | Base form rules. Buffer works yet starts to weaken. |

- One decade in ratio moves pH by one unit.

- Keep pH within ±1 of pKa for reliable resistance to acid or base.

- Use the same unit for both concentrations. The ratio cancels units, the math stays clean.

How to choose the right pKa

Pick a buffer with a pKa close to your target pH. This sounds obvious yet it prevents half of all headaches. Biological work often favors HEPES, MOPS, PIPES, Tris, or phosphate groups because their pKa values straddle physiological ranges and their side reactions are modest.

Temperature affects pKa for many systems. Tris shifts about −0.028 pH units per °C. If you set a buffer at 4 °C then run at 25 °C the pH will drift. Check the supplier’s technical sheet or an authoritative handbook before you commit.

Common mistakes to avoid

- Mixing units across inputs. Enter [A⁻] in mM then [HA] in µM and the ratio goes off by a thousand. Use the same unit for both.

- Using total buffer concentration by accident. You need the species concentrations at equilibrium. After mixing acid and base forms the numbers change.

- Ignoring temperature drift. Many lab buffers move with temperature. Adjust pKa or set pH at the final working temperature.

- Trusting pH meters without calibration. Two fresh buffers for two-point calibration keep the readings honest.

- Chasing infinite precision. Buffers tame variation but they don’t freeze pH at a thousandth of a unit. Focus on significant digits that matter to your assay.

A short detour on buffer capacity

Henderson–Hasselbalch gives you the target composition. Capacity tells you how well the buffer resists change. The capacity rises with total buffer concentration and peaks near pH ≈ pKa. If your reaction throws strong acid or base you may need either a higher total concentration or a different buffer pair with a pKa closer to the stress point. This is why good recipes publish both the components and their molarities.

How to prepare a buffer in the lab

Here’s a practical path that works for most weak acid/base systems. You can adapt the quantities to your volume.

- Pick your pair and pKa. Aim for pKa within one unit of the target pH.

- Choose the total buffer concentration. Many biological buffers run from 10 mM to 100 mM.

- Use the calculator to get the ratio. Compute r = 10^(pH − pKa).

- Split the total concentration. If CT is total:

- [A⁻] = CT · r / (1 + r)

- [HA] = CT / (1 + r)

- Weigh or measure reagents. Dissolve the base form and acid form to reach those concentrations in roughly 90% of your final volume.

- Check pH at the working temperature. Adjust with small aliquots of acid or base forms of the buffer, not strong HCl or NaOH unless the recipe calls for it.

- Bring to final volume and mix. Re-check pH since dilution can change activity slightly.

Safety note: wear eye protection and gloves when working with acids, bases, or powdered reagents.

FAQ

What’s the difference between pKa and Ka?

Ka expresses dissociation as an equilibrium constant. pKa is simply −log₁₀(Ka). Small pKa means strong acid for that step of dissociation.

Can I use the calculator for polyprotic acids?

Yes for single buffer regions tied to a specific dissociation step. Pick the pKa that matches the pair you use. Phosphoric acid has three pKa values so choose pKa₂ when you use H₂PO₄⁻/HPO₄²⁻ for example.

Does ionic strength matter?

It can. Activity coefficients change with ionic strength which nudges apparent pKa. In most teaching labs or routine prep the effect is small. High-precision work benefits from tables adjusted for ionic strength.

What happens if [A⁻] equals [HA]?

The ratio equals 1 so log₁₀(1) equals 0. pH equals pKa. This is the sweet spot for buffer capacity.

How accurate are pH predictions?

The equation assumes ideal behavior. Real solutions deviate a little. Use the calculation to set your starting point then fine-tune with a calibrated pH meter at the working temperature.

Further reading

- LibreTexts: The Henderson–Hasselbalch Equation

- PubChem for compound data including pKa entries in many records

How this calculator helps in real workflows

In quality control a buffer out of spec can derail an assay so teams need a quick way to verify the numbers. In teaching labs students often arrive with different units, concentrations, or even Ka instead of pKa. The calculator accepts both, converts everything behind the scenes, and returns values in a consistent format with the ratio clearly listed.

Researchers who tweak conditions day to day appreciate the ability to swap inputs at will. Enter pH and pKa to see the target split between acid and base. Enter both concentrations and pKa to confirm pH before the measurement step. You can export a CSV from the results panel and paste it into your electronic lab notebook with the exact settings you used.

Step-by-step checklist for troubleshooting buffers

- Verify the chemical forms you used. Sodium acetate ≠ acetic acid.

- Confirm the pKa value for your working temperature.

- Check the total ionic strength if your system is sensitive.

- Re-measure concentrations after mixing. Dilution changes the numbers.

- Make sure both species are present in the same concentration unit.

- Compute the ratio with the calculator to see if your mixture matches the intent.

Glossary in plain language

- Conjugate base: the deprotonated partner that accepts a proton when acid is added.

- Weak acid: an acid that doesn’t completely dissociate in water.

- Buffer: a mixture that resists pH swings when small amounts of acid or base appear.

- pH meter offset/drift: small shifts due to aging electrodes or temperature changes.

- Aliquot: a measured portion of a solution that you add or remove.

Mini guide: converting between Ka and pKa

| Known | Find | Equation | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ka | pKa | pKa = −log₁₀(Ka) | If Ka = 1.8×10⁻⁵ then pKa = 4.744 |

| pKa | Ka | Ka = 10^(−pKa) | If pKa = 6.35 then Ka = 4.47×10⁻⁷ |

Why the calculator reports the ratio too

The ratio gives you intuition at a glance. If the ratio equals 1 the buffer sits at its most symmetric point. If the ratio hits 10 the mixture leans heavily toward the base. Seeing the ratio prevents configuration mistakes like swapping the acid and base entries or mixing unit scales.

Accessibility and reproducibility

All outputs in the results panel use tabular numerals so numbers line up in neat columns. You can export the table to CSV then re-import it into your notes or spreadsheet. This tiny step helps colleagues repeat your setup with the exact same inputs which protects your time later when questions appear.

The Henderson–Hasselbalch equation remains a small gem tucked into every chemist’s toolkit. It’s quick. It’s transparent. It guides buffer design without heavy computation. Use the calculator to plan mixtures, predict pH, or back-calculate the composition of a solution that already sits on your bench. Then validate with a calibrated meter and you’re ready to run.